[Notes] Zero to One by Peter Thiel

Preface

- Long lasting companies go from 0 to 1 instead of 1 to n.

- Each innovation is new & different - the next Mark Zuckerberg won't create a social network.

- If you're copying from these guys, you're not learning from them.

Chapter - 1: The Challenge of the Future

What important truth do very few people agree with you on?

- Brilliant thinking is rare, but courage is in even shorter supply than genius.

- A good answer looks something like: "Most people believe in x, but the truth is the opposite of x."

- Good answers to this contrarian question are as close as we can come to looking into the future.

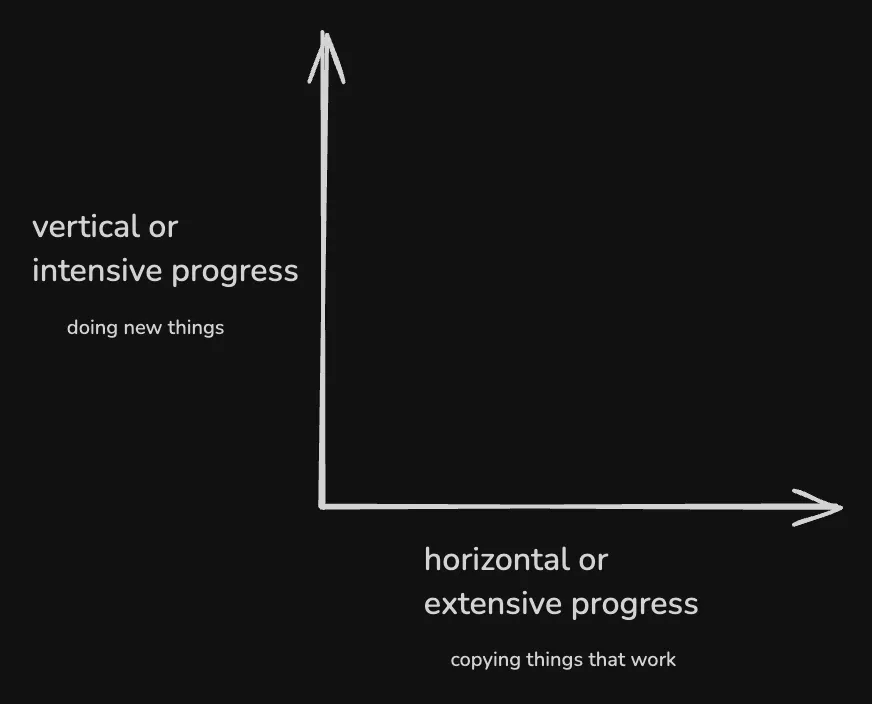

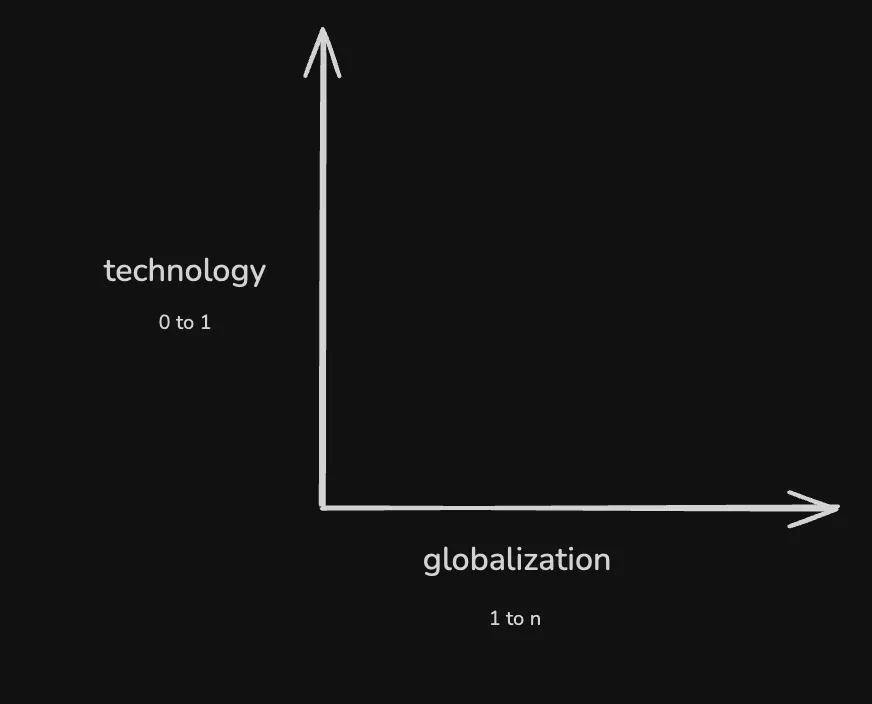

- The single word for vertical, 0 to 1 progress is technology.

In a world of scarce resources, globalization without new technology is unsustainable.

New technology tends to come from new ventures - startups.

It's hard to develop new things in big organizations, and it's even harder to do it by yourself.

A lone genius might create a classic work of art or literature, but he could never create an entire industry.

You need to work with other people to get stuff done, but you also need to stay small enough so that you actually can.

Chapter - 2: Party Like It's 1999

If you can identify a delusional popular belief, you can find what lies hidden behind it: the contrarian truth.

The distortions caused by bubbles don't disappear when they pop.

The first step to thinking clearly is to question what we think we know about the past.

The lessons that stuck from the dot-com crash that still guide business thinking:

- Make incremental advances.

- Grand visions inflated the bubble, so they should not be indulged.

- Anyone who claims to be able to do something great is suspect.

- Anyone who wants to change the world should be more humble.

- Small incremental steps are the only way forward.

- Stay lean & flexible.

- All companies must be 'lean', which is code for 'unplanned'.

- Planning is arrogant & inflexible. Instead you should try things out, iterate, and treat entrepreneurship as agnostic experimentation.

- Improve on the competition.

- Don't try to create a new market prematurely.

- The only way to know you have a real business is to start with an already existing customer.

- So, you should build your company by improving on recognizable products already offered by successful competitors.

- Focus on product, not sales.

- If your product requires advertising or sales to sell it, it's not good enough.

- Technology is primarily about product development, not distribution.

- The only sustainable growth is viral growth.

- However, the opposite principles are probably more correct:

- It is better to risk boldness than triviality.

- A bad plan is better than no plan.

- Competitive markets destroy profits.

- Sales matters just as much as product.

- To build the next generation of companies, we must abandon the dogmas created after the crash.

- Not all of the opposites are true, but one must ask: How much of what we know about business is shaped by mistaken reactions to past mistakes?

The most contrarian thing of all is not to oppose the crowd but to think for yourself.

Chapter - 3: All Happy Companies Are Different

- The business version of the contrarian question is:

What valuable company is nobody building?

Creating value is not enough, you also need to capture some of the value you create.

Under perfect competition, in the long run no company makes an economic profit.

A monopoly owns its market, so it can set its own prices.

Capitalism and competition are opposites. Capitalism is premised on the accumulation of capital, but under perfect competition all profits get competed away.

If you want to create and capture lasting value, don't build an undifferentiated commodity business.

Monopolists lie to protect themselves. They know that bragging about their great monopoly invites being audited, scrutinized, & attacked.

Non-monopolists tell the opposite lie: "we're in a league of our own."

The fatal temptation is to describe your market extremely narrowly so that you dominate it by definition.

Non-monopolists exaggerate their distinction by defining their market as the intersection of various smaller markets.

Whereas, the Monopolists disguise their monopoly by framing their market as the union of several large markets.

The problem with a competitive business is that you have to fight hard to survive. You'll need to squeeze out every efficiency.

The competitive ecosystem pushes people toward ruthlessness or death.

A monopoly is different. since it doesn't have to worry about competitors, it has wider latitude to care about its workers, its products, and its impact on the wider world.

A business that is successful enough can take ethics seriously without jeopardizing its own existence.

In business, money is either an important thing or everything.

Monopolists can afford to think about things other than making money.

In perfect competition, a business is so focused on today's margins that it can't possible plan for a long-term future.

Only one thing can allow a business to transcend the daily brute struggle for survival: monopoly profits.

Creative monopolists give customers more choices by adding entirely new categories of abundance to the world.

Even the government knows this, that's why one of its departments works hard to create monopolies by granting new patents even though another part hunts them down by prosecuting antitrust cases.

The promise of years or even decades of monopoly profits provides a powerful incentive to innovate.

In business, equilibrium means stasis, and stasis means death.

In a competitive industry, the death of your business doesn't matter as some other undifferentiated competitor will always be ready to take your place.

In the real world, each business is successful exactly to the extent that it does something others cannot.

Monopoly is the condition of every successful business.

- All happy companies are different: each one earns a monopoly by solving a unique problem.

- All failed companies are the safe: they failed to escape competition.

Chapter - 4: The Ideology of Competition

Professors downplay the cutthroat culture of academia, but managers never tire of comparing business to war.

We use headhunters to build up a sales force that will enable us to take a captive market and make a killing.

But really, it's competition, not business, that is like war: allegedly necessary, supposedly valiant, but ultimately destructive.

Inside firms, people become obsessed with their competitors for career advancement.

The firms themselves become obsessed with their competitors in the marketplace.

People lose sight of what matters and focus on their rivals instead.

Rivalry causes us to overemphasize old opportunities and slavishly copy what has worked in the past.

If you can't beat a rival, it may be better to merge.

Sometimes you do have to fight. When that's true, you should fight and win. There is no middle ground: either don't throw any punches, or strike hard and end it quickly.

If you're less sensitive to social cues, you're less likely to do the same things as everyone else around you. You'll be less afraid to pursue your own activities single-mindedly and thereby become incredibly good at them.

Then, when you apply your skills, you're less likely than others to give up your own convictions: this can save you from getting caught up in crowds competing for obvious prizes.

If you can recognize competition as a destructive force instead of a sign of value, you're already more sane than most.

Chapter - 5: Last Mover Advantage

- Even a monopoly is only a great business if it can endure in the future.

- The value of a business today is the sum of all the money it will make in the future.

- You also have to discount those future cash flows to their present worth.

- A given amount of money today is worth more than the same amount in the future.

- It takes time to build valuable things, and that means delayed revenue.

- For a company to be valuable it must grow and endure.

Will this business still be around a decade from now?

- Numbers alone won't tell you the answer: instead you must think critically about the qualitative characteristics of your business.

There are four characteristics of a monopoly:

- Proprietary Technology:

- The proprietary technology must be at least 10 times better than its closest substitute in some important dimension.

- Anything less than an order of magnitude better will probably be perceived as a marginal improvement and will be hard to sell, especially in an already crowded market.

- The clearest way to make a 10x improvement is to invent something completely new.

- If you build something valuable where there was nothing before, the increase in the value is theoretically infinite.

- Or you can radically improve an existing solution: once you're 10x better, you escape competition.

- Network Effects:

- Network effects make a product more useful as more people use it.

- Network effects can be powerful, but you'll never reap them unless your product is valuable to its very first users when the network is necessarily small.

- Some technologies work at scale, but only at scale.

- Paradoxically, then, network effects businesses must start with especially small markets.

- The initial markets are so small that they often don't even appear to be business opportunities at all.

- Economies of Scale:

- A monopoly business gets stronger as it gets bigger.

- Service businesses especially are difficult to make monopolies.

- A good startup should have the potential for great scale build into its first design.

- Branding:

- A company has a monopoly on its own brand by definition, so creating a strong brand is a powerful way to claim a monopoly.

- However, beginning with brand rather than substance is dangerous.

- No technology can be built on branding alone.

Building a Monopoly:

- Choose your market carefully and expand deliberately.

- Start small and monopolize:

- Every startup should start with a very small market as it is easier to dominate a small market than a large one.

- The perfect target for a startup is a small group of particular people concentrated together and served by few or no competitors.

- In practice, a large market will either lack a good starting point or it will be open to competition.

- Scaling Up:

- Once you create and dominate a niche market, then you should gradually expand into related and slightly broader markets.

- Sequencing markets correctly is underrated, and it takes discipline to expand gradually.

- The most successful companies make the core progression - to first dominate a specific niche and then scale to adjacent markets - a part of their founding narrative.

- Don't Disrupt:

- Originally, disruption was a term of art to describe how a firm can use new technology to introduce a low-end product at low prices, improve the product over time, and eventually overtake even the premium products offered by incumbent companies using older technology.

- If you think of yourself as an insurgent battling dark forces, it's easy to become unduly fixated on the obstacles in your path.

- Indeed, if your company can be summed up by it's opposition to already existing firms, it can't be completely new and it's probably not going to become a monopoly.

- Disruptors are people who look for trouble and find it. Disruptive companies often pick fights they can't win.

- As you craft a plan to expand into adjacent markets, don't disrupt: avoid competition as much as possible.

- The Last Will Be First

- Moving first is a tactic, not a goal. What really matters is generating cash flows in the future.

- It is much better to be the last mover - to make the last great development in a specific market and enjoy the years or even decades of monopoly profits.

- The way to do that is to dominate a small niche and scale up from there, toward your ambitious long-term vision.

You must study the endgame before everything else.

Chapter - 6: You Are Not a Lottery Ticket

Does success come from luck or skill?

- If success were mostly a matter of luck, these kinds of serial entrepreneurs probably wouldn't exist.

- Success is never accidental.

- There is no way to settle this debate objectively. Every company starts in unique circumstances, and every company starts only once.

- Statistics don't work when the sample size is one.

- In the early ages, luck was something to be mastered, dominated, and controlled.

- Everyone agreed that you should do what you could, not focus on what you couldn't.

- No one pretended that misfortune didn't exist, but prior generations believed in making their own luck by working hard.

"Shallow men believe in luck, believe in circumstances... Strong men believe in cause & effect."

- Ralph Waldo Emerson

"Victory awaits him who has everything in order - luck, people call it."

- Roald Amundsen

- If you believe your life is mainly, a matter of chance, why are you even reading this?

"Is the future a matter of chance or design?"

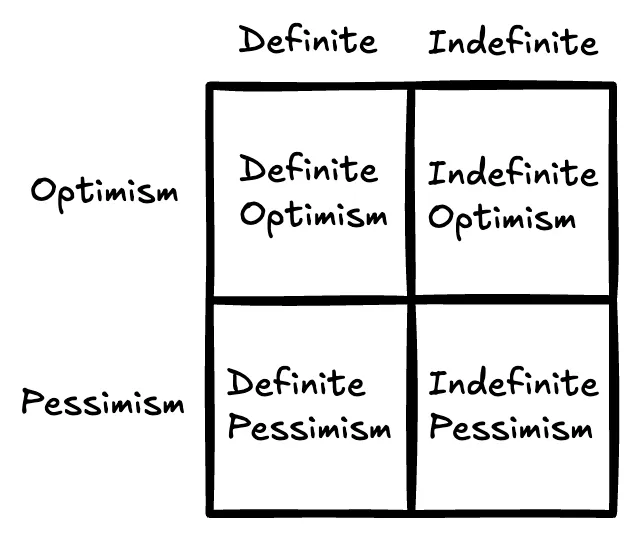

- You can expect the future to take a definite form or you can treat it as hazily uncertain.

- If you treat the future as something definite, it makes sense to understand it in advance and to work to shape it.

- But if you expect an indefinite future ruled by randomness, you'll give up on trying to master it.

Indefinite Pessimism:

- An indefinite pessimist looks out onto a bleak future, but he has no idea what to do about it.

- The indefinite pessimist can't know whether the inevitable decline will be fast or slow, catastrophic or gradual. All he can do is wait for it to happen.

Definite Pessimism:

- A definite pessimist believes the future can be known, but since it will be bleak, he must prepare for it.

Definite Optimism:

- To a definite optimist, the future will be better than the present if he plans and works to make it better.

- Earlier, people welcomed big plans and asked whether they would work.

- Big plans for the future have become archaic curiosities.

- Big plans for the future are too important to be left to the experts.

Indefinite Optimist:

- To an indefinite optimist, the future will be better, but he doesn't know how exactly, so he won't make any specific plans.

- He expects to profits from the future but sees no reason to design it concretely.

- Instead of working for years to build a new product, indefinite optimists rearrange already-invented ones.

Only in definite future is money a means to an end, not the end itself.

We are more fascinated today by statistical predictions of what the country will be thinking in a few weeks' time than by visionary predictions of what the country will look like 10 or 20 years from now.

Definite optimism works when you build the future when you build the future you envision.

Definite pessimism works by building what can be copied without expecting anything new.

Indefinite pessimism works because it's self-fulfilling: if you're a slacker with low expectations, they'll probably be met.

Indefinite optimism seems inherently unsustainable: how can the future get better if no one plans for it.

Progress without planning is what we call 'evolution'.

Would-be entrepreneurs are told that nothing can be known in advance: we're supposed to listen to what customers say they want, make nothing more than a MVP, and iterate our way to success.

But leanness is a methodology, not a goal.

Iteration without a bold plan won't take you from 0 to 1.

A company is the strangest place of all for an indefinite optimist: why should you expect your own business to succeed without a plan to make it happen?

In startups, intelligent design, not evolution, works best.

What would it mean to prioritize design over chance?

- The greatest thing Jobs designed was a business. Apple imagines & executed definite multi-year plans to create products & distribute them effectively.

- Jobs saw that you can change the world through careful planning, not by listening to focu group feedback or copying others' success.

- The power of plannings explains the difficulty of valuing private companies.

- Founders only sell when they have no more concrete visions for the company, in which case the acquirer probably overpaid.

- Definite founders with robust plans don't sell, which means the offer wasn't high enough.

- A startup is the largest endeavour over which you can have definite mastery.

- You can have agency not just over your own life, but over a small and important part of the world.

- It begins by rejecting the unjust tyranny of Chance. You are not a lottery ticket.

Chapter - 7: Follow the Money

- Money makes money.

- Pareto principle or power law: 20% of efforts result in 80% of the outcome.

- Power law distributions are so big that they hide in plain sight.

- The biggest secret in venture capital is that the best investment in a successful fund equals or outperforms the entire rest of the fund combined.

- Only invest in companies that have the potential to return the value of the entire fund. This is a scary rule, because it eliminates the vast majority of possible investments.

- Because rule one is so restrictive, there can't be any other rules.

- VCs must fund the handful of companies that will successfully go from 0 to 1 and then back them with every resource.

- Every single company in a good venture portfolio must have the potential to succeed at vast scale.

- Whenever you shift from the substance of a business to the financial question of whether or not it fits into a diversified hedging strategy, venture investing starts to look a lot like buying lottery tickets.

- And once you think you're playing the lottery, you've already psychologically prepared yourself to lose.

- Life is not a portfolio: not for a startup founder, and not for any individual. An entrepreneur cannot 'diversify' himself.

- He cannot run dozens of companies at the same time and hope that one of them works out well.

- An individual cannot diversify his own life by keeping dozens of equally possible careers in ready reserve.

- You should focus relentlessly on something you're good at doing, but before that you must think hard about whether it will be valuable in the future.

- The power law means that differences between companies will dwarf the differences in roles inside companies.

- If you do start your own company, you must remember the power law to operate it well.

- The most important things are singular: One market will probably be better than all others. One distribution strategy usually dominates all others. Time & decision-making themselves follow a power law, and some moments matter far more than others.

- You cannot trust a world that denies the power law to accurately frame your decisions for you, so what's most important is rarely obvious.

- In a power law world, you can't afford not to think hard about where your actions will fall on the curve.

Chapter - 8: Secrets

Every one of today's most famous and familiar ideas was once unknown and unsuspected.

Every correct answer to what valuable compane is nobody building? is necessarily a secret: something important and unknown, something hard to do but doable.

If there are many secrets left in the world, there are probably many world-changing companies yet to be started.

Four social trends have rooted out belief in secrets:

- Incrementalism:

- From an early age, we're taught that the right way to do things is to proceed one very small step at a time, day by day, grade by grade.

- If you over-achieve and end up learning something that's not on the test, you won't receive any credit for it.

- Risk aversion:

- People are scared of secrets because they are scared of being wrong.

- If your goal is to never make a mistake in your life, you shouldn't look for secrets.

- The prospect of being lonely but right - dedicating your life to something that no one else believes in - is already hard. The prospect of being lonely and wrong can be unbearable.

- Complacency:

- Social elites have the most freedom and ability to explore new thinking, but they seem to believe in secrets the least.

- Why search for a new secret if you can comfortably collect rents on everything that has already been done?

- Flatness:

- As globalization advances, people perceive the world as one homogeneous, highly competitive marketplace: the world is 'flat'.

- Anyone who might have had the ambition to look for a secret will first ask himself: if it were possible to discover something new, wouldn't someone from the faceless global talent pool of smarter and more creative people have found it already?

- Today, you can't start a cult. Forty years ago, people were more open to the idea that not all knowledge was widely known.

- Very few people take unorthodox ideas seriously today, and the mainstream sees that as a sign of progress.

- But the existence of financial bubbles shows that markets can have extraordinary inefficiencies. (And the more people believe in efficiency, the bigger the bubbles get.)

- You can't find secrets without looking for them. There are many more secrets left to find, but they will yield only to relentless searchers.

- Great companies can be build on open but unsuspected secrets about how the world works.

- Only by believing in and looking for secrets could you see beyond the convention to an opportunity hidden in plain sight.

- Secrets about people are relatively under-appreciated. Maybe that's because you don't need a dozen years of higher education to ask the questions that uncover them: What are people not allowed to talk about? What is forbidden or taboo?

- Who should you tell the secrets if you find any? Whoever you need to, and no more.

- In practice, there's always a golden mean between telling nobody and telling everybody - and that's a company.

- Every great business is build around a secret that's hidden from the outside.

- A great company is a conspiracy to change the world; when you share your secret, the recipient becomes a fellow conspirator.

Chapter - 9: Foundations

Thiel's Law: a startup messed up at its foundation cannot be fixed.

Beginnings are special. They are qualitatively different from all that comes afterward.

Companies are like countries in this way: bad decisions made early on are very hard to correct after they're made.

As a founder, your first job is to get the first things right, because you cannot build a great company on a flawed foundation.

When you start something, the first & most crucial decision you make is whom to start it with.

It's unromantic to think soberly about what could go wrong, so people don't.

But if the founders develop irreconcilable differences, the company becomes the victim.

Founders should share a prehistory before they start a company together - otherwise they're just rolling dice.

Freud, Jung, & every other psychologist has a theory about how every individual mind is divided against itself, but in business at least, working for yourself guarantees alignment.

It's very hard to go from 0 to 1 without a team.

Executives who manage companies and directors who govern them have separate roles to play.

You need good people who get along, but you also need a structure to help keep everyone aligned for the long term.

To anticipate likely sources of misalignment, distinguish between:

- Ownership: who legally owns a company's equity?

- Possession: who actually runs the company on a day-to-day basis?

- Control: who formally governs the company's affairs?

A typical startup allocates ownership amount founders, employees, and investors.

The managers and employees who operate the company enjoy possession.

A board of directors, usually comprising founders and investors, exercises control.

Big corporations are prone to misalignment, especially between ownership and possession.

Starts are small enough that founders usually have both ownership and possession, hence most conflicts erupt between ownership and control - that is, between founders and investors on the board.

The potential for conflict increases over time as interests diverge.

In the boardroom, less is more: the smaller the board, the easier it is for the directors to communicate, to reach consensus, and to exercise effective oversight.

However, that very effectiveness means that a small board can forcefully oppose management in any conflict.

Even one problem director will cause you pain, and may even jeopardize your company's future.

A board of three is ideal. Your board should never exceed five people, unless your company is publicly held.

Actually, a huge board will exercise no effective oversight at all; it merely provides cover for whatever microdictator actually runs the organization.

If you want that kind of free rein from your board, blow it up to giant size. If you want an effective board, keep it small.

As a general rule, everyone you involve with your company should be involved full-time.

Sometimes you'll have to break the rule - eg. it usually makes sense to hire outside lawyers and accountants.

Anyone who doesn't own stock options or draw a regular salary from your company is fundamentally misaligned.

They'll be biased to claim value in the near term, not help you create more in the future - that's why it hiring consultants doesn't work.

Even working remotely should be avoided, because misalignment can creep in whenever colleagues aren't together full-time, in the same place, every day.

For people to be fully committed, they should be properly compensated.

A company does the better the less it pays the CEO.

A high pay incentivizes him to defend the status quo along with his salary, not to work with everyone else to surface problems and fix them aggressively.

If a CEO doesn't set an example by taking the lowest salary in the company, he can do the same thing by drawing the highest salary.

So long as that figure is still modest, it sets an effective ceiling on cash compensation.

High cash compensation teaches workers to claim value from the company as it already exists instead of investing their time to create new value in the future.

Any kind of cash is more about the present than the future.

Startups don't need to pay high salaries because they can offer something better: part ownership of the company itself.

Equity is the one form of compensation that can effectively orient people toward creating value in the future.

Giving everyone equal shares is usually a mistake: every individual has different talents, responsibilities, and opportunity costs. So equal amounts will seem arbitrary and unfair.

Resentment at this stage can kill a company, but there's no ownership formula to perfectly avoid it.

So, it is better to keep the details of compensation secret.

People often find equity unattractive. If that company doesn't succeed, it's worthless.

Equity is a powerful tool precisely because of these limitations.

Anyone who prefers owning a part of your company to being paid in cash reveals a preference for the long term.

Equity can't create perfect incentives, but it's the best way for a founder to keep everyone in the company broadly aligned.

Only at the very start of a company do you have the opportunity to set the rules that will align people toward the creation of value in the future.

The founding lasts as long as a company is creating new things, and it ends when creation stops.

If you get the founding moment right, you can do more than create a valuable company: you can steer its distant future toward the creation of new things instead of the stewardship of inherited success. You might even extend its founding indefinitely.

Chapter - 10: The Mechanics of Mafia

What would the ideal company culture look like?

- "Company culture" doesn't exist apart from the company itself: no company has a culture, every company is a culture.

- A startup is a team of people on a mission, and a good culture is just what that looks on the inside.

- Why work with a group of people who don't even like each other?

- Since time is your most valuable asset, it's odd to spend it working with people who don't envision any long-term future together.

- You need people who are not just skilled on paper but who will work together cohesively after they're hired.

- The first four or five might be attracted by large equity stakes or high-profile responsibilities.

- Why should the 20th employee join your company?

Why would someone join your company as its 20th engineer when he could go work at Google for more money and prestige?

- Stock options, work environment, challenging problems to be solved, etc. are bad answers as every company gives those.

- The only good answers are specific to your company, so you won't find them in this book.

- You'll attract employees you need if you can explain why your mission is compelling: not why it's important in general, but why you're doing something important that no one else is going to get done.

- However, even a great mission is not enough. You should be able to explain why your company is a unique match for an employee personally. If you can't, it's probably not the right match.

- Above all, don't fight the perk war. Just cover the basics and then promise what no others can: the opportunity to do irreplaceable work on a unique problem alongside great people.

- From the outside, everyone in your company should be different in the same way.

- On the inside, every individual should be sharply distinguished by his work.

- Startups have to move fast, so individual roles can't remain static for long.

- Job assignment aren't just about the relationship between workers and tasks; they're also about relationships between employees.

- Defining roles reduces conflict. Eliminating competition makes it easier for everyone to build the kinds of long-term relationships that transcend mere professionalism.

- Internal peace is what enables a startup to survive at all.

- When a startup fails, we often imagine it succumbing to predatory rivals in a competitive ecosystem. But every company is its own ecosystem, and factional strife makes it vulnerable to outside threats.

- The best startups might be considered slightly less extreme kinds of cults.

- The biggest different is that cults tend to be fanatically wrong about something important. People at a successful startup are fanatically right about something those outside it have missed.

- Better to be called a cult - or even a mafia.

Chapter - 11: If You Build It, Will They Come?

Engineers are biased toward building cool stuff rather than selling it. But customers will not come just because you built it. You have to make that happen, and it's harder than it looks.

People overestimate the relative difficulty of science and engineering, because the challenges of those fields are obvious. What nerds miss is that it takes hard work to make sales look easy.

The best product doesn't always win. If you've invented something new but you haven't invented an effective way to sell it, you have a bad business - no matter how good the product.

Superior sales and distribution by itself can create a monopoly, even with no product differentiation. The converse is not true.

Two metrics set the limits for effective distribution:

- The total net profit that you earn on average over the course of your relationship with a customer (Customer Lifetime Value, or CLV) must exceed the amount you spend on average to acquire a new customer (Customer Acquisition Cost, or CAC).

- In general, the higher the price of your product, the more you have to spend to make a sale - and the more it makes sense to spend it.

If your average sale is seven figures or more, every detail of every deal requires close personal attention.

But this kind of 'complex sales' is the only way to sell some of the most valuable products.

Since complex sales requires making just a few deals each year, a salesperson can use that time to focus on the most crucial people - and even to overcome political inertia.

Complex sales works when you don't have "salesmen" at all.

At a high enough price point, buyers want to talk to the CEO, not the VP of sales.

Businesses with complex sales models succeed if they achieve 50% to 100% year-over-year growth over the course of a decade.

Good enterprise sales strategy starts small, as it must: a new customer might agree to become your biggest customer, but they'll rarely be comfortable signing a deal completely out of scale with what you've sold before.

Once you have a pool of reference customers who are successfully using your product, then you can begin the long and methodical work of hustling toward even bigger deals.

The challenge here isn't about how to make any particular sale, but how to establish a process by which a sales team of modest size can move the product to a wide audience.

Distribution is the hidden bottleneck.

Marketing & advertising work for relatively low-priced products that have mass appeal but lack any method of viral distribution.

Advertising can work for startups, too, but only when your customer acquisition costs and customer lifetime value make every other distribution channel uneconomical.

Startups should resist the temptation to compete with bigger companies in the endless contest to put on the most memorable TV spots or the most elaborate PR stunts.

No early-stage startup can match big companies' advertising budgets.

A product is viral if its core functionality encourages users to invite their friends to become users too.

The ideal viral loop should be as quick and frictionless as possible. They have extremely short cycle times.

Whoever is first to dominate the most important segment of a market with viral potential will be the last mover in the whole market.

Try to get the most valuable users first.

Power Law: One of these methods is likely to be far more powerful than every other for any given business.

If you can get just one distribution channel to work, you have a great business. If you try for several but don't nail one, you're finished.

Your company needs to sell more than its product. You must also sell your company to employees and investors.

Clamor and frenzy are very real, but they rarely happen without calculated recruiting and pitching beneath the surface.

Selling your company to the media is also necessary.

You should never assume that people will admire your company without a public relations strategy. The press can help attract investors and employees.

Any prospective employee worth hiring will do his own diligence; what he finds or doesn't find when he googles you will be critical to the success of your company.

If you don't see any salespeople around you, you're the salesperson.

Chapter - 12: Man and Machine

- Computers are complements for humans, not substitutes.

- The most valuable business of coming decades will be build by entrepreneurs who seek to empower people rather than try to make them obsolete

- People compete for jobs and for resources; computers compete for neither.

- Gains from trade are greatest when there's a big discrepancy in competitive advantage, but the global supply of workers willing to do repetitive tasks for an extremely small wage is extremely large.

- The start differences between man and machine mean that gains from working with computers are much higher than gains from trade with other people.

- We don't trade with computers any more than we trade with livestock or lamps.

- Computers are tools, not rivals.

- Complementarity between computers and humans isn't just a macro-scale fact. It's also the path to building a great business.

If humans and computers together could achieve dramatically better results than either could attain alone, what other valuable businesses could be built on this core principle?

- Indefinite fears about the far future shouldn't stop us from making definite plans today.

Chapter - 13: Seeing Green

- Seven questions every business must answer:

- The Engineering Question: Can you create breakthrough technology instead of incremental improvements?

- The Timing Question: Is now the right time to start your particular business?

- The Monopoly Question: Are you starting with a big share of a small market?

- The People Question: Do you have the right team?

- The Distribution Question: Do you have a way to not just create but deliver your product?

- The Durability Question: Will your market position be defensible 10 and 20 years into the future?

- The Secret Question: Have you identified a unique opportunity that others don't see?

- A great technology company should have proprietary technology an order of magnitude better than its nearest substitute.

- It's hard to recover from a radically inferior starting point.

- People are so used to exaggerated claims that you'll be met with skepticism when you try to sell it. Only when your product is 10x better can you offer the customer transparent superiority.

- Find the correct/relevant market to gauge your company accurately because you can't dominate a submarket if it's fictional.

- Never invest in a tech CEO that wears a suit. The best sales is hidden. There's nothing wrong with a CEO who can sell, but if he actually looks like a salesman, he's probably bad at sales and worse at tech.

- The world is not a laboratory: selling and delivering a product is at least as important as the product itself.

- Every entrepreneur should plan to be the last mover in his particular market.

Ask yourself: what will the world look like 10 and 20 years from now, and how will my business fit in?

- Great companies have secrets: specific reasons for success that other people don't see.

- Bright futures described using broad conventions never pan out.

- Social Entrepreneurship: this philanthropic approach to business starts with the idea that corporations and nonprofits have until now been polar opposites.

- However, if something is "socially good," is it good for society, or merely seen as good by society?

- Doing something different is what's truly good for society - and it's also what allows a business to profit by monopolizing a new market.

- The best projects are likely to be overlooked, not trumpeted by a crowd; the best problems to work on are often the ones nobody else even tries to solve.

Elon Musk: "If you're at Tesla, you're choosing to be at the equivalent of Special Forces. There's the regular army, and that's fine, but if you're working at Tesla, you're choosing to step up your game."

- An entrepreneur can't benefit from macro-scale insight unless his own plans begin at the micro-scale.

- No sector will ever be so important that merely participating in it will be enough to build a great company.

- A valuable business must start by finding a niche and dominating a small market.

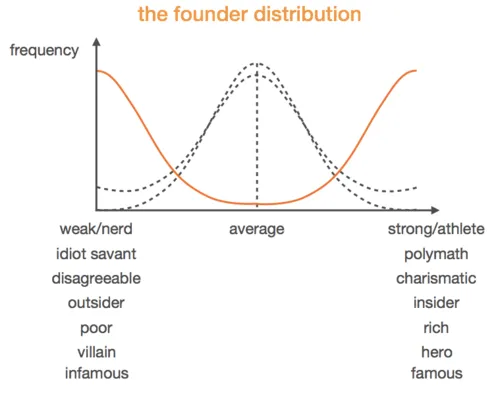

Chapter - 14: The Founder's Paradox

- It's more powerful but at the same time more dangerous for a company to be led by a distinctive individual instead of an interchangeable manager.

- Whatever the great individuals in history were actually like, the mythologized versions of them remember only the extremes.

Like founders, scapegoats are extreme and contradictory figures.

On the one hand, a scapegoat is necessarily weak; he is powerless to stop his own victimization.

On the other hand, as the one who can defuse conflict by taking the blame, he is the most powerful member of the community.

These are the roots of monarchy: every kind was a living god, and every god a murdered king.

For some fallen stars, death brings resurrection.

Highly visible success can attract highly focused attacks.

Jobs return to Apple 12 years later shows how the most important task in business - the creation of new value - cannot be reduced to a formula and applied by professionals.

Apple's value crucially depended on the singular vision of a particular person.

A unique founder can make authoritative decisions, inspire strong personal loyalty, and plan ahead for decades.

We should be more tolerant of founders who seem strange or extreme; we need unusual individuals to lead companies beyond mere incrementalism.

The lesson for founders is that individual prominence and adulation can never be enjoyed except on the condition that it may be exchanged for individual notoriety and demonization at any moment - so be careful.

- Founders are important not because they are the only ones whose work has value, but rather because a great founder can bring out the best work from everybody at his company.

- The single greatest danger for a founder is to become so certain of his own myth that he loses his mind.

- But an equally insidious danger for every business is to lose all sense of myth and mistake disenchantment for wisdom.

Conclusion: Stagnation or Singularity

- Without new technology to relieve competitive pressures, stagnation is likely to erupt into conflict.

- We cannot take for granted that the future will be better, and that means we need to work to create it today.